Spent two weeks in Davos re-learning how to ski, hiking in snow peaks and generally embracing all that the wonderful resort town has to offer. To me, Davos is known for two things – alpine skiing and the annual World Economic Forum.

I’ve always wondered why Davos was chosen by the World Economic Forum (WEF) as the venue since its first meeting in 1971. There are many other venues around the world for such events but why a Swiss ski resort town?

Here in the highest town in Europe at over 1,500 m (5,000 ft) above sea level, thousands of delegates from around the world congregate every February in wintry conditions to discuss economic growth and cooperation for their global elite members’ club of bankers, industrialists, oligarchs, technocrats and politicians.

Before Davos became an annual destination for the rich and powerful, it was an obscure agrarian community of farmers living in rudimentary conditions in one of the many Swiss mountain valleys. Winters were harsh and the locals were definitely not skiing to pass their time. However, by the end of the 19th century, it became a kind of Shangri-La in the Swiss Alps where people from faraway came in search of hope and recreation.

Here is what I found about Davos’ fascinating past.

There was a German exile and former revolutionary who fled to Switzerland in the mid-1800s. His name was Alexander Spengler. He studied medicine at the University of Zurich and found a job as a country doctor in Davos, then a poor, remote and isolated hamlet, completely different from the rich and intellectual city he was used to. Missing the better life, Spengler went on with his work nonetheless.

At that time, there was an outbreak of tuberculosis throughout Switzerland but Spengler recorded not a single case in Davos. He also observed that the locals were able to climb steep mountain paths “without perspiring or becoming breathless.” He was convinced that the mountain climate in Davos had a healing effect and started to treat patients with great success. The incredible discovery spread far and wide among physicians and patients and Davos became a highly recommended place for convalescence for lung disease patients.

From the first two patients in the winter of 1865, the number of international visitors grew to over half a million by the turn of the century, and Davos was set to become a world-famous resort with new development of infrastructure, promenades and luxurious sanitoriums with stunning views of snow-covered peaks towering over the gentle valley.

One of the most famous visitors was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, who became the first British citizen to cross the Maienfelder Furgga pass above Davos on skis. Little know about Doyle was that he was a ski pioneer at his time as skiing was then an unknown sport and considered extremely dangerous. Doyle wrote about his winter experience for the Strand Magazine in 1894 and invariably inaugurated the trend of alpine skiing in the continent. To a certain extent, it was the British who introduced and popularised alpine skiing in Switzerland.

In 1930 Zurich engineer Ernst Gustav Constam designed and patented the T-bar ski lift which was constructed in the Davos Bolgen practice area. A world first, it was instantly a media sensation and attracted 70,000 skiers in its first year alone. The T-bar is still widely used today in ski resorts around the world though chair lifts and cable cars bring skiers to greater heights faster and catering to more people.

Davos was also the inspiration for one the most influential 20th century literature “The Magic Mountain” by Thomas Mann who won the Nobel Prize for Literature five years after the novel was published. Magic Mountain’s protagonist was sent to Davos for a course of treatment for tuberculosis at the health resort – “in the high-altitude sanatorium there he encountered a bourgeoisie weary of civilisation, people who cultivated ennui and wallowed in their own suffering. They played patience, listened to chamber music, tended to their stamp collections, and stuffed themselves with cakes and chocolate. The introspective world of these sanatoria enclosed a strange ‘mixture of death and amusement’”.

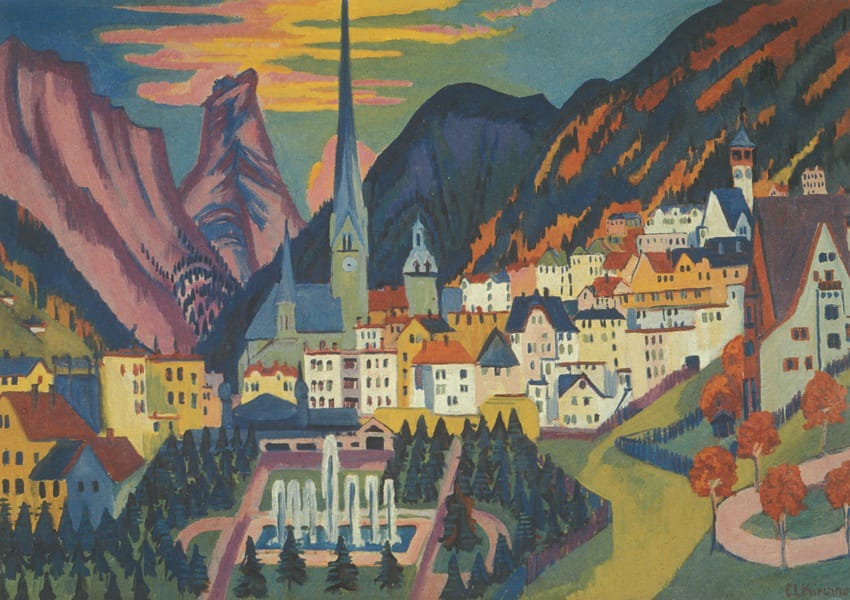

Another famous Davos resident was German Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, one of the most notable Expressionist artists, who painted the lives of the people and the beauty of his adopted home. Kirchner wrote “This is a country in which democracy has become reality. Here a man’s word still counts, and you need have no fears about sleeping with your doors open. I am so happy to be allowed to be here, and through hard work I should like to thank the people for the kindness they have shown me.” Unfortunately Kirchner, troubled with the impending German aggression on its neighbours, eventually took his own life in 1938.

Fast forward to 1971, three decades after World War II, the establishment of United Nations, the European Union, a German engineer and economist Klaus Martin Schwab brought together top business and academic leaders, thinkers and strategists from around the world to Davos for the first European Management Symposium which was renamed the World Economic Forum.

According to the organisation’s internal history – Davos, the setting of Thomas Mann’s Der Zauberberg (The Magic Mountain), was a place of recreation and relaxation, where people took in clean mountain air to restore their health and recharge their minds. Schwab wanted participants in the European Management Symposium to feel relaxed enough to speak frankly, while maintaining camaraderie of purpose and mutual respect. This became known as the “Davos Spirit”, still the hallmark of all Forum gatherings. Nobody, not even Klaus Schwab, after this first symposium could be aware of the powerful platform that had been created.

On a wintry February day, I stood outside the Davos Congress Centre where two weeks ago was overwhelmed with world leaders, dignitaries, intellects, media, front-runners, back-roomers, armed security, delegates and wannabes.

It’s so quiet now.

Looking around, I realized the distinct blue and yellow Davos coat-of-arms that reminded me of a country still at war one year after the first air strike from its norther neighbor. Soaking in for a moment trying to feel the intense exploration of ideas and plans to improve global economy for the next twelve months.

How will the world change this time next year?

Joan Yap